- News

- News Archives

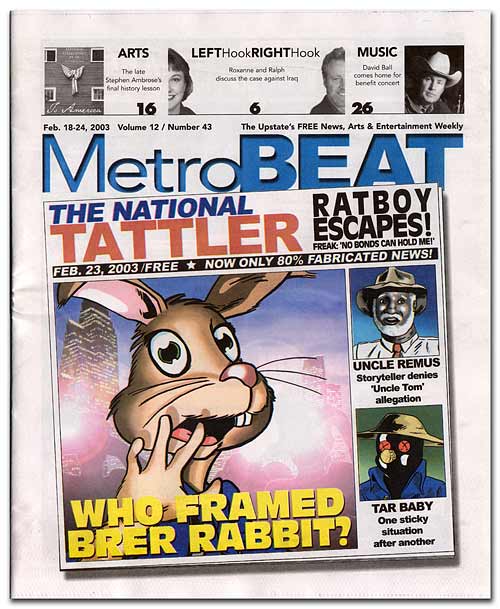

MetroBEAT: Who Framed Brer Rabbit?

This article was originally published in print and was previously available online.

You can also read the complete transcript of my interview with Chris Haire.

FEBRUARY 19, 2003

Who Framed Brer Rabbit?

The truth about Disney’s classic & controversial Song of the South

BY CHRIS HAIRE

Rabbit Runs Afoul of the Law

(Knight Rider) Toontown, U.S.A. — Toontown police have arrested motion picture star Brer Rabbit outside of his home in nearby Briar Patch in connection with an international smuggling ring. Authorities report that Rabbit was the head of a criminal organization which funneled bootleg copies of the Walt Disney classic Song of the South into the United States.

According to police, the ring purchased legal VHS and laserdisc copies of the film from retailers in Great Britain and Japan and then smuggled them into the US, where distribution of the film has been “banned” since 1986.

Following his release this morning, Rabbit held a press conference where he denied any connection to the smuggling ring. In fact, he’s taking it all in stride. After all, this isn’t the first time he’s been in a sticky situation. “I was born and raised in the briar patch,” Rabbit said.

Rabbit’s lawyer, Uncle Remus, says his client is innocent of any wrongdoing and he will prove it in court. “It’s the truth. It’s actual,” Remus says. “Everything is satisfactual.”

An undisclosed source close to the investigation claims that Rabbit may have been set up by former associates Brer Fox and Brer Bear.

Previously, Rabbit had been involved in studio lot altercation with female co-star Tar Baby. The actress sued, but the case was settled out of court for an undisclosed sum.

•••

Song of the South is one of Walt Disney’s most celebrated films. It’s also one of its most controversial.

For many, the film, which is based on the Uncle Remus stories of Georgia-native Joel Chandler Harris, is simply a heartwarming tale about a young white boy named Johnny and the kindly old black man who befriends him. Throughout the movie, Uncle Remus serves as a surrogate parent and mentor to young Johnny. Uncle Remus’ method of instruction: stories about Brer Rabbit, Brer Fox and Brer Bear.

Originally released in 1946, the film has been praised as a landmark cinematic achievement for its successful synthesis of live-action and animation. (The segments featuring Uncle Remus and Johnny, the grandson of plantation owners, are live-action, while the segments depicting Brer Rabbit and company are animated.) A song from the film, “Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah,” won the Academy Award for Best Song in 1948 and has since gone on to be one of Disney’s most famous hits. The star of the film, James Baskett, also won a honorary Oscar in 1948 for his portrayal of Uncle Remus.

Although the film remains popular, Song of the South has never been released on video in the States, and it hasn’t been shown at movie theaters since 1986. Since then, rumors have sprung up regarding the movie, the most popular being that the movie was banned by Disney following a boycott by the NAACP. Another claims that Bill Cosby bought the rights to the movie and refuses to release it. Both are untrue.

However, the demand for Song of the South remains high. As such, a grassroots movement of sorts continues to fight for the re-release of the film. Their method of appeal: petitions and letters. Meanwhile, others have no desire to wait for Disney to change its mind. They turn to overseas vendors where the Song of the South was released on video, or they turn to black marketeers selling bootleg copies of the movie at flea markets and conventions and over the Internet. Up until 2001, Disney sold Song of the South video cassettes in the UK in a format not recognized by American VHS players. The film was also available in Japan on laserdisc. But make no mistake, purchasing a copy comes at a price, sometimes as high as $300 or more.

Stateside, Disney continues to profit from Song of the South in one form or the other. You can still purchase a video entitled Singalong Songs: Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah. The packaging for the video even features James Baskett as Uncle Remus. And if you go to Disney World, you and yours can hop on Splash Mountain, a log ride based on Song of the South. It features audio-animatronic versions of Brer Rabbit, Brer Fox and Brer Bear. The Tar Baby and Uncle Remus are noticeably absent. Recently, Disney released a set of pins which featured Brer Rabbit, Brer Fox and Brer Bear and a set of figurines commemorating Walt Disney’s 100th birthday featuring the same. The official Disney website also has a link to the film; however, it notes that the film is unavailable. (At press time, Disney had not responded to questions about their reluctance to release Song of the South.)

With this in mind, it’s easy to see that Disney hasn’t abandoned Song of the South just yet. It may very well be released one day.

So what’s all the hubbub about?

The film’s detractors say it presents an idealized vision of the Old South. It is a world where whites live in expansive plantation homes and blacks in charming little shacks. It is a world where blacks joyfully work in the fields, spurred on to work not by the threat of the lash, but by the cheerful songs in their hearts. It is a world that never existed.

One problem with Song of the South concerns exactly when it takes place. Is it pre- or post-Civil War? According to Karl Cohen, author of Forbidden Animation, the film clearly takes place after the Civil War. “Disney did not make it clear that it was after the Civil War,” Cohen says. “Part of the confusion is that he [Walt Disney] was warned by the censors in Hollywood who read the scripts, the Hayes Office, to please make it clear that the film takes place in the 1870s or 1880s. He did not do that. They suggested that he open it with a card that said ‘Georgia’ and a date. He ignored that, and so you don’t know when it took place.”

As such, many are left to wonder if Uncle Remus and his fellow African Americans are slaves or free men and women? “What I enjoy talking to my students about the film is its deep confusion about the time period that it is supposed to represent, and that is both tricky in Uncle Remus and the movie,” says Susanna Ashton, professor at Clemson University and a specialist in post-Civil War literature. “The film has some people who are wearing costumes that are clearly Edwardian, that are clearly from the 1890s. But then you look at the movie and all of the people are in hoop skirts and pretty clearly everybody is a slave, so clearly we’re in a pre-Civil War era.”

Arguments over settings aside, let’s be honest here. Song of the South may be a charming family film, but the fact that some folks find it offensive shouldn’t come as a shock to anyone. Even its fans recognize the trouble spots.

“It’s simple. It has racist elements,” Cohen says. “When Disney made it, he didn’t realize that he was making something quite volatile as it could be. If anything, the basic problem is with Disney. He was insensitive.”

The problem for Cohen: the live-action segments of the film present a beautiful, idyllic world where whites live in mansions and work indoors, while blacks live in lovely, little shacks and work in the fields all day long, singing songs and carrying on. Make no mistake about it: the whites are in charge, and the blacks bow and scrape before their masters. “It comes across as a idealized master/slave relationship for the people who see it,” Cohen adds. “[Disney] found it to be a very beautiful, sympathetic depiction of the South, but he didn’t realize that his depiction was a Southerner’s depiction.”

R. Bruce Bickley Jr., an English professor at Florida State University and author of Joel Chandler Harris: A Biography and Critical Study also acknowledges the trouble with Song of the South. “Disney does kind of a whitewash of the stories in the Song of the South. I’m afraid that a lot of people who think they know these stories know Disney’s five animated tales,” says. “There the Uncle Remus character is very much kissing up to ‘massa.’ [He’s] a cooperative sort of figure, not as complicated a figure by far as the Uncle Remus in Harris’ stories.”

The film also overlooks the more rebellious and anarchist overtones of the original tales where slaves are represented by the meeker creatures Brer Rabbit, Brer Possum and Brer Tarrypin, while the ruling whites are represented by the predators, Brer Fox, Brer Bear and Brer Wolf.

Christian Willis is the webmaster behind SongoftheSouth.net (www.songofthesouth.net), so you know he’s a fan. But he’s also well aware of the troublesome representation of blacks in the film. “Overall, I believe the charge is valid, although a bit exaggerated,” Willis says. “It should be noted first and foremost that this movie was not set in antebellum times, so any act of servitude is not as a slave, but as a servant. This is very important in explaining the attitudes of the African Americans throughout the movie.”

Potentially offensive or not, the film tries to be true to the times it depicts, although in a sanitized, family-friendly sort of way. “It cannot be denied that this movie was created with subservient roles for the African Americans because that was the general mindset of not only the time in which it was filmed, but also the time in which the movie depicts,” Willis says.

Still, the relationship between blacks and whites may be viewed as progressive for its time. For starters, you can look at the relationship between Uncle Remus and Johnny — that of teacher and student, surrogate father and son. Of particular importance is how Uncle Remus is portrayed. “The boy [Johnny] looks up to Uncle Remus as a role model no more than the way we look up to our own role models,” says James McKimson, the man behind the Uncle Remus Pages (www.uncleremuspages.com). “Uncle Remus is portrayed as an older man full of wisdom. He is more like a father figure that enjoys telling stories and making things right. He is not portrayed as a negative character.”

For Willis, Remus is not as subservient as much as he is polite. “Uncle Remus may bow slightly and remove his hat in the presence of a woman, but that was common respect shown by all civilized men, regardless of race.”

For Courtney Cromwell, a Song of the South fan who runs Brer Rabbit Stew (www23.brinkster.com/brerrabbit), the character of Uncle Remus is no Uncle Tom. “He is shown as being one of the wisest people on the plantation,” Crowell says. “His stories help the children learn important lessons, and more often than not, he ends up being right.”

Hints of the equality between the races are evident in other ways. “I am especially fond of the moments shared between Uncle Remus and Miss Doshy [Johnny’s grandmother], where their common interest for Johnny transcends any racial barrier, and you see two mature human beings talking to one another,” says Willis. “Yes, it’s brief, but it’s there. I’d say these were pretty good steps for a movie depicting the Old South created in the 1940’s.”

It’s also important to remember that Disney was trying to make a family film, not a historically accurate account of the Old South. “Disney did the best they could to keep this film a family movie. We really didn’t see any violence between slaves and their masters or any racial slurs,” says McKimson. “You didn’t see any discipline, which made them look like free individuals that could do anything they wanted. People know life on the plantation wasn’t as joyful as depicted in the movie, but you have to remember it’s a family movie.”

In many ways, Disney was simply doing what he had always done: producing sanitized, family-friendly versions of popular stories. Many of these stories, like the Grimm Brother’s “Snow White” and “Cinderella,” were oftentimes violent and grotesque. Disney had no problem discarding these undesirable elements. After all, his films were made with 5-years-olds in mind. “Some people feel as if Disney doesn’t portray plantation life correctly. They want to see sinister plantation owners who treat their slaves like dirt,” Courtney Crowell says. “[T]his is Disney. People don’t complain when Ariel doesn’t kill herself at the end of The Little Mermaid like she does in the original tale. It’s the same concept.”

For some critics, the trouble with Brer Rabbit and company extend well-beyond Song of the South, all the way back to the man who originally published the tales, Joel Chandler Harris, and the character he created — Uncle Remus.

Harris was a journalist for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution during the post-Civil War years. The 180-plus Uncle Remus stories Harris compiled were based on tales he had heard from slaves as a teenager. “Harris luckily had a darn good ear. He was able to transcribe these stories and capture the dialect, and thank goodness. Even the black critics who are upset with Harris’s white man’s treatment of black slavery narratives are still thankful that somebody captured these stories and brought so much attention to them,” Bickley says.

Altough Harris was enamored with these African American folk tales, he was by no means a champion of equal rights. “He had the standard white prejudices,” Bickley says. “He couldn’t see mixed marriages. He couldn’t see mixed classrooms.”

Despite his prejudices, Harris also had his progressive side. “He was one or two or three of the most important journalists who came out of the Civil War and helped us think through Reconstruction and all of its bad consequences to address the Negro problem,” Bickley says. “Harris said, ‘We have to get our act together. We have to accept who we are now. We have to accept the humanity of our black former slaves who are now citizens like we are.’”

Even though some critics commend Harris’ efforts to collect African American folklore, they disapprove of the one character Harris did create — Uncle Remus. Unlike Brer Rabbit, Brer Fox, Brer Bear and even the Tar Baby, Uncle Remus was solely the creation of Harris, and it was Harris who gave the character his more Uncle Tom-like qualities. Like Harris, “Uncle Remus has his prejudices against uppity blacks pushing too hard, too fast,” Bickley says.

However, these critics may be missing the point. Like Brer Rabbit, Harris’ Uncle Remus may also be a trickster. And by extension, Harris. “The cagiest character in the Uncle Remus stories is Uncle Remus himself,” Bickley says. “Sure, he seems content on the old plantation. But in the stories, he tells about the inner life of what it is to be a slave in a power structure dominated by the stronger critters.”

In the debate over Song of the South and the Uncle Remus stories, it’s this identification that is often overlooked. “The black folk narrators, both male and female, identified with Brer Rabbit, Brer Possum, Brer Tarrypin... as the wily folk heroes. They don’t look very threatening. They’re not anything anybody would think twice about, but they are fast and fast-witted,” Bickley says. “Even though they’re not physically stronger, their wits help them be survivors, so they’re always out-tricking the would-be tricksters.”

According to Bickley, the Brer Rabbit tales, as they were told by slaves to slaves, were instructive in nature. “Brer Rabbit uses his head to escape. It sends a message to the slave listeners, ‘Use your head. Don’t be stupid. Don’t fall for these traps. Think before you act and outwit your master,’” Bickley says. “Out of these come a whole tradition of the black slave’s evasion of responsibility, using ruses like, ‘Oh, the plow done broke today. Massa, I can’t do that for you.’ Or, ‘I’m feeling poorly,’ ‘I’m feeling sickly,’ all kinds of strategies for evading the demands of the power structure.”

Another troubling point for both the movie and the stories concerns the Tar Baby. On the surface, the Tar Baby, with its jet black “skin,” is an extremely disconcerting racial stereotype, especially when one considers how the term “tar baby” has been used as a racial epithet. “The trouble with the term ‘tar baby’ is people associate it with the ‘N-word,’” Bickley says. “During Harris’ time and the ‘20s and ‘30s as well, the Tar Baby is associated with any black person or figure.”

For those of you who don’t remember the tale of Brer Rabbit and the Tar Baby, here’s a brief summary as it appears in Harris’ work. Brer Fox makes a female figure out of tar, and he sets it on the side of the road. His goal: to catch and kill uppity ole Brer Rabbit. Eventually, Rabbit comes along and greets the Tar Baby. The Tar Baby doesn’t respond. Rabbit continues to say hello to the Tar Baby, but he fails to get a reply. Angered, Rabbit attacks the Tar Baby. He gets stuck. Fox emerges. He takes Rabbit and starts to plot how he’s going to kill Rabbit. Being the quick-witted trickster that he is, Rabbit tells Fox he can do anything he likes to Rabbit but throw him in the briar patch. Of course, Fox throws Rabbit in the briar patch, Rabbit’s home turf. Rabbit is safe. He has once again escaped danger.

The story is quite simple on the surface, but Bickley says that the tale is pretty heady stuff, especially when you consider matters of race. In case you forgot, Brer Rabbit is black. “It’s a famous piece of reverse psychology,” Bickley says. “If you try to fight your own blackness, you get trapped in it. You have to deal with it. It’s really complex stuff.”

He adds, “It’s a term for a dealing with your own identity.”

While the segment with the Tar Baby is probably the most famous animated sequence in Song of the South, it’s safe to say Disney failed to recognize its deeper meaning. In fact, he completely gets it wrong, ignoring the complex racial allegory in favor of kindergarten didacticism. In the movie, Brer Rabbit represents Johnny, with Brer Fox and Brer Bear, representing two bullies who pick on the boy.

Disney also misrepresented the Uncle Remus tales in ways which glossed over the tales’ more rebellious connotations. In the adaptation from page to screen, the violent, revenge-oriented nature of the stories was toned down. In Harris’ work, not only does Brer Rabbit lose some of his children at the hands of his enemies, but ultimately, Brer Rabbit orchestrates the deaths of his enemies Brer Fox, Brer Bear and Brer Wolf, the symbolic representations of the white master. In one tale Brer Rabbit feeds Brer Fox’s head to Fox’s own children. In another, Brer Rabbit kills Brer Wolf by locking him in the cellar and pouring boiling water on him. “I’ve done an index of the plots and themes of these stories, and like 40% of the stories of both of his first books are about predatory violence, revenge-taking, loss of limb, physical punishment, death. Harris wasn’t afraid to transmit these stories from his black sources,” Bickley says.

In the end, Song of the South has its flaws. There is no argument there. But does it really deserve to sit on a shelf until the end of time? The folks interviewed for this story don’t think so. After all, we can learn about the history of motion pictures and the history of America by watching this film. Through it, we can see where we came from, where we’ve been and where we are now. “This is an historical film that needs to be preserved,” Christian Willis says. “Not only can future generations learn from the Uncle Remus stories, but [they] can learn how we have progressed in filmmaking, both racially and through the techniques used to combine live-action with animation.”

Karl Cohen, for one, hopes that day is just around the bend. “There will come a day when people aren’t upset and threatened by these stereotypes from the past. They recognize them as such, and say, ‘This is an old film. Let’s recognize it for its merits,’ ” Cohen says.

“But until that happens it’s going to stay in the closet.”